Intimacy is the most influential space between human beings – and the new front in the battle between tech giants.

So says Yuval Harari, whose book Nexus, predicted what is unfolding now as millions of us develop intimate relationships with AI bots, agentic assistants and obsessively use the likes of ChatGPT in our personal and working lives. Privacy, shmizacy!

But for health and social care this territory war may offer a silver lining. Bots and AI assistants will get to know our innermost fears and anxieties in ways that even our closest family members can't. And this, particularly for men, famously reluctant to share worries, could open up significant routes into preventative healthcare.

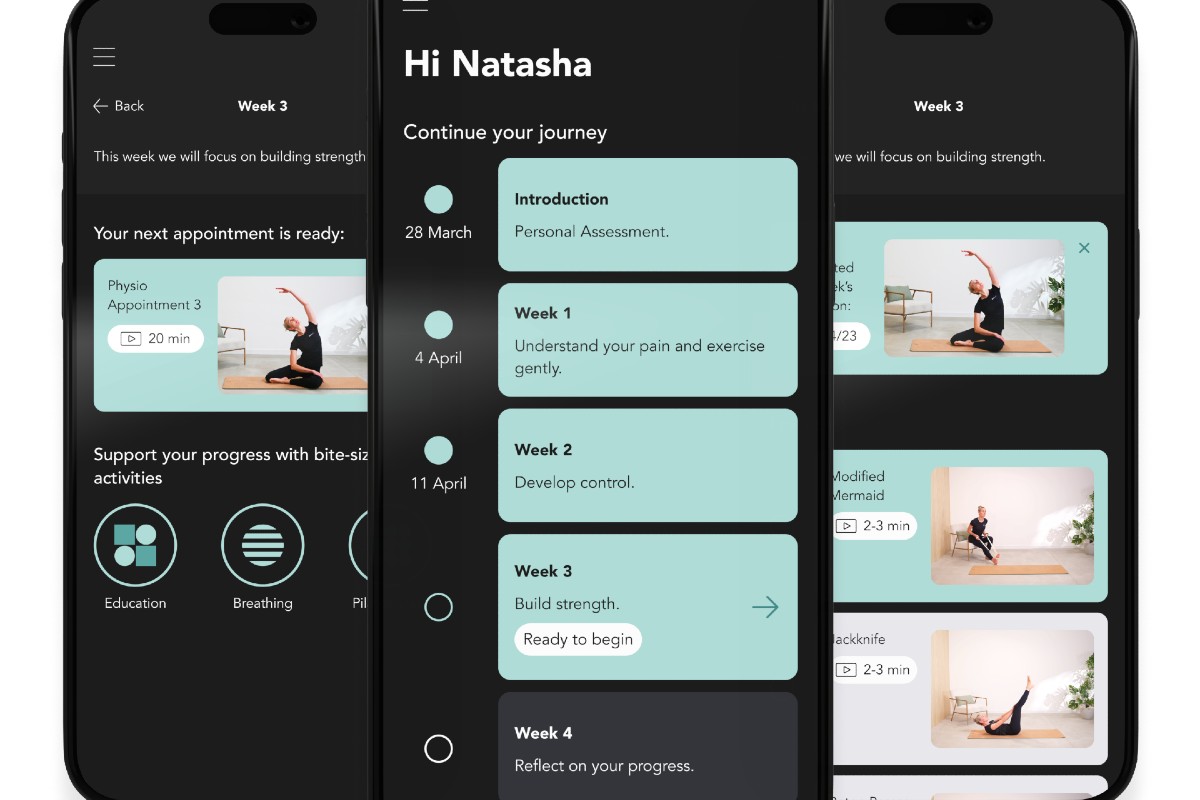

As any good listener will know, the things we worry about are not usually revealed through random blurting. All too often, subtle clues emerge in our choice of words, awkward silences, shifts in our tone or speed of speaking and when we avoid talking about things altogether. Listening is a long game and GPs don't always have the time to digest such subtleties with endless queues eating up their mental bandwidth.

But AI bots have all the time in the world. They are available to us in every one of the 168 hours in every week. Their attention is limitless. And by ‘listening' to us, they accrue vast amounts of data enabling them to build ‘intimate relationships' with us. Of course, these are not ‘real' – they lack reciprocity, vital in human-to-human relationships. But this reciprocity gap doesn't stop us feeling close to our pets, worrying about them and grieving when we lose them. As of now, all this data goes to the tech companies, which, unsurprisingly, turns it to commercial advantage. Anyone doubting this stratagem should read Shoshana Zuboff's The age of surveillance capitalism. But since we're now, as a country, in bed with the technocracy, supplying government support for AI data centres, should we be looking to secure a health and social care feed from agentic AI to the NHS and local government?

This could work at two levels. The first is relatively uncontroversial. The Government could get a weekly macro feed – here are the things that people are worrying about in Britain today. It could be cut by region, sex, religion, sexual orientation, age, class or whatever. These data will be available. This kind of report could enable macro planning – the things we need to get ready for, region by region. It could be a taking the temperature of the nation product.

The second level is far more controversial and might involve allowing trusted public health people to have a gateway into our AI relationships. We'd have to consent to it, of course. But it could mean the things we worry about, fears about our health, for example, and about which we are reluctant to speak, could be accessed by our GP or other trusted health professionals. For some this would be 1984 – for others, welcome reassurance.

Of course, there would need to be strict controls on access. ‘Are you thinking what we're thinking?' could become ‘I actually know what you're thinking this very minute'. Scary stuff, indeed, if personal data was able to be used for political purposes. Controls would need to be put in place for those times when benevolent governments may be less so.

The upside is knowing that someone could be looking out for our health and potentially warning us when our health is in danger of deteriorating, as well as giving us the heads-up on emerging pandemics and other threats. When our bot-mates are suggesting things we could do to be healthier, we might just listen and act – ‘friends' can be important influencers. Our AI mates might tell us the things that our friends would never dare.

But lurking at the back of my mind is another fear: If this could be done now, then it may already be happening. How would you know? Never forget the leadership precept: ‘It's better to ask for forgiveness than permission.'

Anxiety about these kind of things can impact our health so if it worries you and you have an AI mate, you could ask them – you never know, they may know.